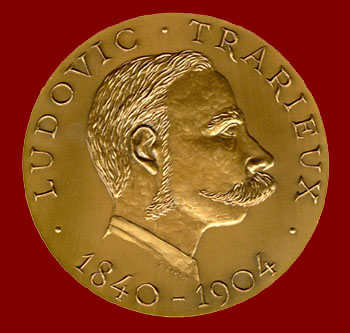

| LUDOVIC TRARIEUX | HISTORICAL ACCOUNT | 1985 : THE FIRST PRIZE | PRIZE 2015 | Le Livre d'Or | INFORMATION

|

|

ARCHIVES

HOMMAGE TO NELSON MANDELA

Ludovic-Trarieux Prize Winner 1985

DOWNLOAD :"A TRIBUTE to NELSON MANDELA" pdf ![]()

The Jury of the "Ludovic Trarieux" Prize, assembled for the first time on March 29, 1985, in the Room of the Council of the order ofthe Bordeaux Bar Council, proceeded to the designation of the laureate of the First International Human Rights Prize Ludovic-Trarieux ".

In the first voting round have been obtained :

Nelson Mandela (South Africa): 8 votes

Adanan Arabi (Syria) 1 vote

Abdelrrahim Berrada (Morocco) 1 vote

Lukanienko (USSR): 1 vote.

The Ludovic Trarieux Prize 1985 has been awarded to :

NELSON MANDELA (South Africa)

The Jury of the 1st Ludovic Trarieux Prize 1985 was composed of :

Jacques Chaban-Delmas, Former French Prime Minister, Mayor of Bordeaux,

Bertrand Favreau, President of the IDHBB,

Adolf Touffait, Judge at the Court of Justice of the European Community

Louis-Edmond Pettiti, Judge at the European Court of Human Rights

Yves Jouffa, President of the French League for the defence of human rights and the Citizen,

And also M. Bernard Jouanneau, Marc Agi, R.L. Larnaudie, Bernard Stasi, Bernard Langlois and Jean Lacouture.

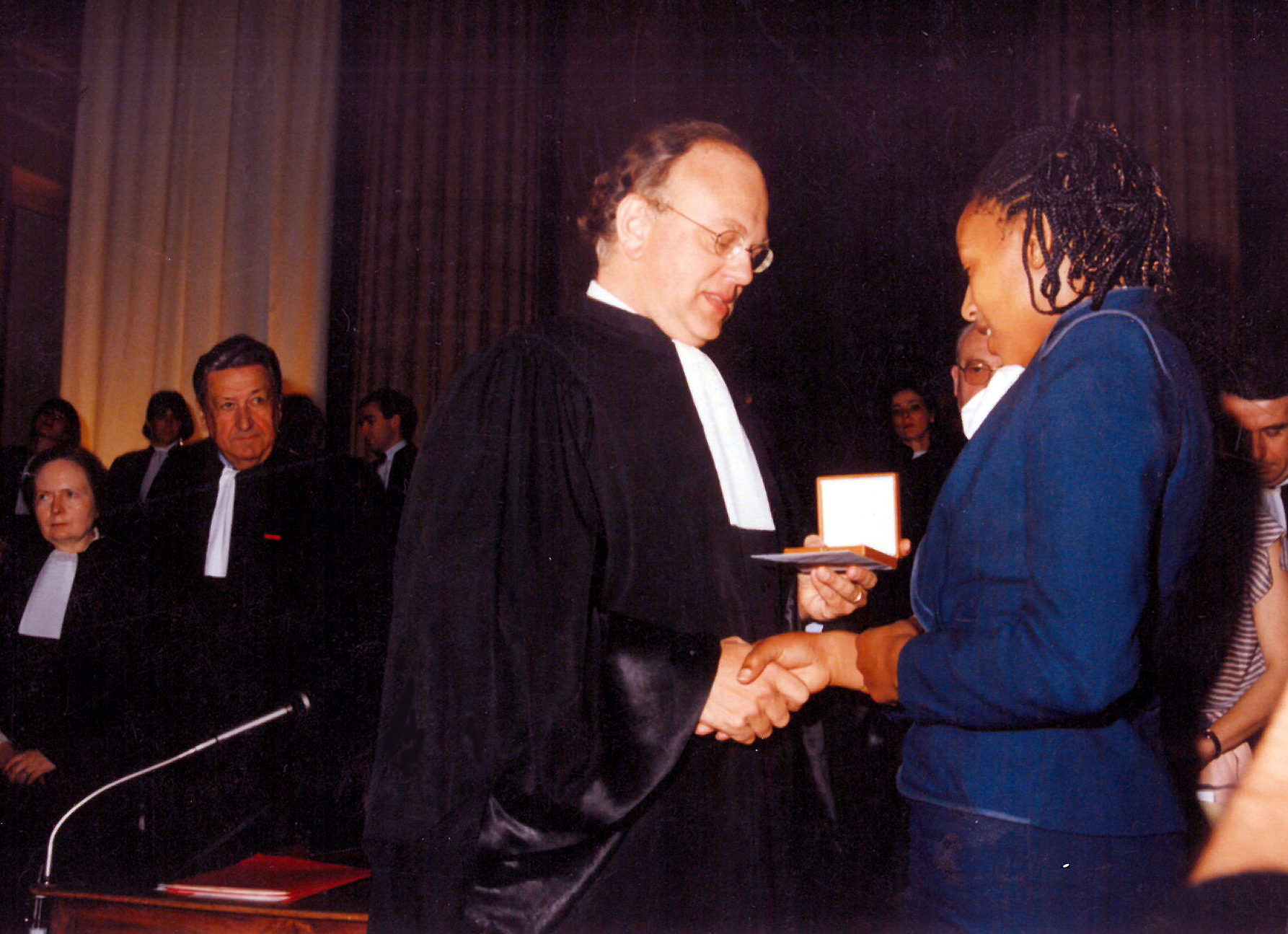

For final assignment, the Rules of the Prize require that the prize-winner should accept it and receive it himself on the occasion of a ceremony award and if he is prevented from coming, that the Prize could be given to a member of his family or to a designated proxy. That is why, Princess Zenani Mandela came from Swaziland to accept and receive the Ludovic Trarieux Prize on behalf of her father.

APRIL 27, 1985 : CEREMONY AWARD OF THE FIRST LUDOVIC-TRARIEUX PRIZE

EXCERPTS OF THE ADDRESS BY MR. BERTRAND FAVREAU, CHAIRMAN OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS INSTITUTE OF THE BORDEAUX BAR (FRANCE)*

" [...] There are countries where the action by which words may be followed can be designed only for the conquest of the right to speak - that right to which we will lay claim as to an unassailable right of the free man.

There are political dreams which cannot be pried into from the watch towers of the concentration camps, or enclosed in their barbed wire. No inescapable fate controls them, and within them there ripens, as with a health-giving sap, nothing but the thirst for freedom.

Such is the significance of the fight being fought by the man we are specially honouring here tonight.

There is a country in the present-day world in which four million îndividuals, whose rights we must respect because, as Jefferson said, the minority enjoys equality of rights and to violate them would be to act as oppressons (1), are denying over twenty million men whose skins are black or "coloured" the right to every form of free speech. And since these four million are alone responsable for making the laws, and make them not merely in their own interest but in almost every case actually to the détriment of those other twenty million who are not entitled to vote with them, we feel inclined to say that the time has now come to abandon words for action.

We too, dear colleagues, have doubtless been feeling we have had enough of speechmaking, conférences and symposiums and that in our own sphere too the defence of human rights must deserve something more; that, as though in the archalc age when the Eupatrids were et the height of their power, we must resume the fight on behalf of those whose Solon has yet to appear on the scene.

This fight is being fought by people who are not figures of ancient history. They are people considered to be unable to express themselves, but, like Aristotle's slaves, they are out to win for themselves the right to speech.

Such, ladies and gentlemen, is the significance of the prize awarded by the jury which has honoured me with its chairmanship to the South African lawyer, Mr. Nelson Mandela. The jury has made its choice et the close of a deliberation conducted as such things should be conducted, conscientiously and scrupulously, in the full knowledge of all the implications of that choice, and this it is which gives so much meaning to its verdict.

Why Nelson Mandela ? No doubt because he is a South African. But even more because he is a lawyer.

For us, being a lawyer has long been partly a matter of vocation. It has also naturally meant acquiring the necessary academic wherewithal. Perhaps we also feel it is above all the possession of some little thing more within oneself. But for Nelson Mandela, the son of a king, born et Umtata between Durban and East London, and brought up among the egalitarian rites and rhythms of the Tembu tribe, where the eiders told storles of "the good old days, before the arrivai of the white man" (2), was it not, considering what his future might normally have been, a very different sort of adventure ?

When at 16 he entered Fort Hare University College, he was emerging from a childhood fed on descriptions of the times when his people, living in peace under the democratic rule of the kings, had "moved freely and confidently up and down the country without let or hindrance" (3). When he chose to pursue his legal studies he was obliged to enter the one university in South Africa to admit Blacks.

He had already committed himseif in fact by privately swearing the oath of which he was to tell his judges when he later stated : "l hoped and vowed that, among the treasures that life might offer me, would be the opportunity to serve my people and to make my own humble contribution to their freedom struggles" (4). And given that his fight for freedom was to take him through the impenetrable mysteries of law, how could his path not have been traced out for him in advance ?

Having taken his law degree and been articled in 1942 to a firm of white lawyers, he was then to become the first black attorney ever to practise in South Africa, subsequently setting up in partnership with Oliver Tambo, a future fellow fighter.

What sort of life was led by the first black lawyer in Johannesburg in 1945 and the years that followed ? He was every day confronted with the merciless ups and downs of racial segregation, both petty and statutory. But in his case the hurt went deeper as a result of his isolation within an exclusively white legal world where, though there was no questionne of his remarkable intellectuel merits, he was no more than tolerated.

One should read Mandela's own account of things. In the intigiacy of his office he sometimes dictated to secretaries who were white. If, while he was engaged in the ordinary process of dictation, a white client happened to come in, the secretary would be seen to get up, drop her pen and block, and seek some way of hiding her embarrassment. One secretary, to show that a Black could not possibly be her employer, would hurriedly rummage in her handbag for a few coins, which she would hand to her boss with the words : "Nelson, please go and fetch me a shampoo !" (5).

Still worse than the lack of considération encountered on the part of the judges, all of whom were white, were the severe measures which hampered his professional activity. As he was to explain later : "l discovered, for exemple, that unlike a white attorney 1 could not occupy business premises in the city unless 1 first obtained ministerial consent... 1 applied for that consent, but it was never granted" (6).

However, by dint of obstinacy Mandela succeeded in obtaining, if not a permit, et least temporary walvers for himself and Oliver Tambo. Once these had expired they were not renewed, and both Mandela and Tambo were instructed to leave the town and to go and practise in a reserve for Blacks in the bantustan corresponding to their ethnic origin. Or aise in what he was to refer to as "the back of beyond", miles away from where clients could reach them during working hours (7). The bitter comment he was to add was not unrelated to the firmness of his détermination. He remarked : "This was tantamount to asking us to abandon our legal practice, to give up the legal service of our people for which we had apent many years training. No attorney worth his sait will agree easily to do so" (8).

"No attorney worth his salt". Mandela, as we cannot but have realized, was most certainly "worth his sait", was certainly one whose commitments were a matter of vocation, of personal conscience. "The whole life of any thinking Atrican in this country drives him continuously to a conflict between his conscience on the one hand and the law on the other. This is not a conflict peculiar to this country. The contact arises for men of conscience... in every country" (9).

How could Mandela have escaped the encounter with a confliet inséparable from the very fact of being, a lawyer, by nature a respectful servant of the law - a conflict between the thirst for treedom and the laws enacted by and for a minority to prevent the majority from making itseif heard ? He found himselt alone, face to face with the Law.

"Vor dem Gesetz steht ein Türhüter" runs a passage in Kafka's The Trial, in the parable interpreted in the coursè of the dialogue between the priest and K. in the chapter entitled "In the Cathedral" (10). "Before the Law stands a doorkeeper on guard. To this door-keeper there comes a man from the country who begs for admittance to the Law. But the door-keeper says that he cannot admit the man et the moment. "

Let us re-read this passage and bear it in our minds. Kafka's man from the country did not anticipera such difficultés. Nor did he expect to find a succession of doorkeepers each more powerful than the preceding one. Should not the Law be accessible to every man and et all times ? However, the man niiively decided to wait for permission to enter.

We know how the story ends. The man waits for days and then for years. He grows old and feeble. Then, as he lies down in front of those doors of the Law which he has never been able to enter he is still just lucid enough to hear the door-keeper say in what for him is no more than a murmur : "No one but you could gain admittance through this door, since the door was intended only for you. 1 am now going to shut it."

Each of us will interpret the story in his own way (11). "Before the Law" the man should have made his choice; he should not have walted. For a lawyer the choice is always a complex one, but it may when all is said be elementary.

The position is straightforward : he must either, because it is the Law, attempt to secure !ta enfoncement in the best possible manner while disapproving of it, or aise fight it because it is unjust in the hope of replacing it by a better Law, with ail the rieks attaching to the break with the existent order.

There have been remarkable exemples of the first alternative. The most outstanding achievement in detence under such conditions was that of Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, a Paris lawyer of the days of the Terror. The Bar as an institution had been abolished and such defence as existed was muzzled; in his hostility to the laws in force and his extreme anxiety to defend et ail costs, he spared no effort to have himself appointed public prosecutor and was suécessfui in doing so. For he fait that this was now the only post et which he could save the accused persons.

A strange prosecutor, indeed, for those days ! Later in his memoirs he was to write : " I had the joy of saving the former nobles and the big landowners 1" (12)

Who, exactly, was Jean-Nicolas Bouilly ?

He was the author of Leonora, from which was derived the libretto to which Beethoven was to compose the magnificent music of Fidelio - referred to by myself on this very platform last year. The ultimate moral of the story is chanted by the chorus as a hymn celebrating the release of prisoners held for their personal convictions : "Es sucht der Brüder seine Brüder und kann er helfen hilft er gem " (13).

But Mandela had no possibility of becoming a judge in order to mitigate in practice laws which he held to be uniust. A black attorney was not entitled to become a judge.

Before the Law ? Thomas Aquinas had already answered the question, and Montesquieu had written : "A thing is not just because it is the law; it must be the Law because it is just" (14).

Mandela, faced with the Law, made his choice; he was against it : "I regarded it as a duty which I owed, not just to my people, but also to my profession, to the practice of law, and to justice for ail mankind, to cry out against this discrimination which is essentially unjust and opposed to the whole basis of the attitude towards justice which is part of the tradition of legal training in this country" (15).

In 1944 he had already, like all young African intellectuels enamoured of freedom and non-violence, joined the African National Congress founded by Albert Luthuli in 1912. Its principles were those advocated by Gandhi for the Indiens of South Africa shortly before leaving the country in 1914 to embark on the career which was to make him famous.

Very naturally Mandela was one of the leaders of the Campaign for the Defiance of Unjust Laws, even becoming its Volunteer-in-Chief and organizing acts of disbedience against six different apartheid laws. The rejoinder was not slow in coming : the government instituted flogging, even for women, as the penalty for the crime of defiance. Mandela was tried under the Suppression of Communism Act. He was given a suspended sentence of nine months; but he had the satisfaction of seeing the argument he had used in his own defence become a part of the grounds on which the court based !ta judgment, since Judge Rumpff declared that the offences with which he was charged had " nothing to do with communisme. (16)

But this was no more than a prelude. The sentence was too lenient; what it was sought to achieve was the most dishonourable penalty possible, namely, disciplinary action by his fellow attorneys.

In 1953 the Transvaal Law Society requested the Supreme Court to declare him barred from practising by reason of the part he had played in the Defiance Campaign, which it held to be incompatible with the rules of étiquette to be observed by an honourable member of the profession. But the attempt was vain. The Supreme Court - to its credit - declared that his activity was in no way an infringement of the rules of conduct whose observance was to be expected of a member of an honourable profession and that he had not exceeded his rights, since it was in no way dishonourable for an attorney to identify himself with his people when that people was fighting for political rights, even though !ta activités might infringe the laws of the country.

Mandela was, and was to remain, a lawyer. Indeed henceforward his calling was to assume a still loftier character : he was destined to assume the defence of one very special client, namely, himself. By an irony of fate he was to act professionally et once as accused and as defence lawyer.

Yet he realized et that time, as did millions of black men and women with him, that no lawyer's office in the world could pride itseif on a clientèle as large as the clientèle he referred to as "his" people. And the client who had initially called him in was a client more demanding still, a client whose name was freedom.

"I was made, by the law, a criminel, not because of what I had done, but because of what I thought, because of my conscience. Can it be any wonder to anybody that such conditions make a man an outlaw of society" (17).

Events now followed one another raplàly and it was growing clear that the days of reckoning were on the way. In 1956 came the trial for treason. lt lasted five years - five yeare during which Mandela spent his days in the dock together with the 156 other nationalists, Albert Luthuli among them, and his evenings working as an attorney et his office. When the other defence lawyers were precluded f rom acting et the trial, Mandela assumed the defence of the others as weil as his own.

The trial turned the tables on the accusers. But the verdict of general acquitter was returned in an atmosphère of general confusion, for a graver event hacl occurred to stupefy the world.

On 21 March 1960, in Sharpeville, in the Southern Transvaal, the police had fired 700 shots et a protest démonstration against the Pass Laws. These are the laws which interfere with the freedom of the Black population to come and go by obliging them on pain of a fine, and because of their colour, to have their special pass constantly on them.

There were 69 fatal casualties among the demonstrators and 178 injured. This time the police had made no pretence of self-defence : 155 of the casualties had been shot in the back.

A tew days later, before the exact number of casualties was known for a certainty, the African National Congress was banned, and Mandela was obliged to go into hiding. He was compelled to abandon his practice, but not his vocation, for the struggle for lust laws was to continue.

"It has not been easy for me during the past period to separate myself from my wife and children, to say good-bye to the good old days when, et the end of a strenuous day at an office, I could look forward to joining my family et the dinner-table, and instead to take up the life of a man hunted continuously by the police, living separated from those who are closest to me, in my own country, facing continually the hazards of detection and of arrest" (18).

And his arrest came, after 17 months in hiding, on 5 August 1962. He was 44 years old. Since then he has never known freedom. His daughters, who were then only children, were to have no memorles of their father as a free man.

But Mandela was not finished with. Two court cases had falled, and the attempt to do away with him had to be resumed twice again.

There were two successive trials. A dialogue of impossibilities, a Kafkaesque dialectic, such as is reflected in the remark made in The Trial : "See... he admits that he doesn't know the Law and yet he claims he's innocent" (19).

But Mandela was not ignorant of the Law; he was contesting it. He was not even referring to the unwritten laws, merely to the laws in force in all the democracles in the world : "We believed in the words of the Universel Declaration of Human Rights, that the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of the Government" (20).

The charges against him were terrifying : communism (once again), and now terrorisme In most instances the legal arguments used were based merely on speclous syllogisme. The communiste it was held, was in the eyes of the law someone who sought to bring about political change through illegal action, and since Mandela was questionne the existent political order he must be a communiste Or again -. the Law defined terrorism as "any activity liable to compromise the maintenance of public order", and since Mandela was acting in such a way as to incite to the perturbing of public order he must be a terroriste

At the close of the trial in Pretoria, which had lasted from 22 October to 7 November 1962, he was sentenced to five years' hard labour for leaving South Africa without a valid passport, and for lnciting African workers to go on strike in March 1961. A light sentence, perhaps, for one who was dally developing into the living personification of the African people. When, on the evening of the verdict, he was seen leaving the old synagogue now used as a court room, the crowd which had gathered notwithstanding the police prohibition calied out Tshotsholoza Mande ! " (Mandela, keep it up !) (21).

There was not the slightest doubt that he would "keep it up" when he was released et the end of the five years. And for this reason, when, in 1963, a year after his conviction, 8 people arrested a few months earlier on a farm in Rivonia were being tried, Mandela was brought out of the Central Prison in Pretoria where he was serving his sentence and placed in the dock together with them.

A recent law had instituted the death penalty for sabotage. And it is true that after Sharpeville the ANC, after 50 years of militant non-violence, had decided to turn to sabotage through the instrumentality of Umkonto, the "spearhead of the nation". Albert Luthuli had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, but in the "homelands" the Blacks were being shot et. Sabotage, however, did not mean terrorism or guerilla warfare, and Mandela made a special point of stressing the distinction. He had by now been in prison for 15 months and had neither shed blood nor fired a shot; he was to resume et this fresh trial his duel role of prisoner and defence lawyer.

Sabotage had been chosen as a means of avoiding loss of human life and of warding off civil war, the nightmare vision of which was haunting a part of the black population. As a means of avoiding the bloodbath of which - unlike the storm which, one March evening, had washed the bloodstained platform in front of the police station et Sharpeville - not ail the storms of Africa would ever be able to cleanse the soil of the homeland.

"I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which ail persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunités... Africans want a just share in the whole of South Africa; they want security and a stake in Society".

A Utopian prospect ? Given the unquestionable complexity of a society both multi-racial and multi-pthnic, how could such harmony be belleved in ? It had been as Utopian to belleve in non-violence as to condemn mere speech-making as invariably useless; but is a Utopie not, after ail, what Malraux described as "the form espoused by the hope of each man's enemies" ? (23).

The trial lasted 7 months and ended with a sentence not of death but of life imprisonment. The prisoners had escaped the supreme penalty, but only as a result of the feeling aroused in the r,3st of the world. The United Nations General Assembly itseif had issued a protest and adopted an appeai for mercy, approved by 106 votes to one - that of South Africa. On the unfurled banners facing them as they left the court building - the last things they were to see - the condernned prisoners read the words : "So long as we live you will not serve your sentence".

Mandela was taken to Cape Town and from there to Robben Island, the jail for political prisoners; it was a former leper colony and thus seemed permanently destined to accommodate those who, in the eyes of the apartheid régime, had skins different from those of the rest.

Should any doubt remain as to whether Mandela was a lawyer to the very end, his statements from the dock are there to testify to the contrary. They are powerful speeches, cast in a single mould, impelled by an unfaltering dialectic, and they contain et once the history of the ANC and the most damning indictment of segregation coupled with a plea for inter-racial brotherhood. They are, and remain, admirable and sometimes heartrending places of prose. They have travelled ail over the world, printed and bound in every language, bearing in general on the cover the one word, Apartheid.

Mandela, from his Island, through the mere fact of his existence, was to continue to defy the government in power. He was to become the most embarrassing prisoner the régime had ever known.

January 1985. He had been in prison for 23 years, yet the slogan : "Free Mandela" was a seditious as ever, and as severely punished. Since 1982 he had been in the Pollsmoor maximum security prison, to which he had been removed as a dangerous influence on the minds of the other political prisoners. And now, after more than twenty years, as a so to world opinion, the offer was made to him to exchange this new prison for town arrest in Transkei, his bantustan, and more drastic still - for a signed statement abjuring his militant action and his struggle. Doubtless those who made the offer were ignorant of the iron law of politics under which a régime with its foundations in racism could not remain in power with Mandela at liberty. They were also ignorant of its very simple corollary, that Mandela could not agree to be set free while "his" people remained enchained.

By 1985 everything was different, yet nothing had changed. Albert Luthuli had died, under house arrest, his rights denied him. After an interval of twenty years Desmond Tutu had become the second anti-apartheld winner of the Nobel Peace Prize; but the régime which stood out for separate development of the two communities was still in power and the Blacks were stili deprived of political rights. Oliver Tambo was the President in Exile of the ANC, whose militants continued to be hanged. And the police were continuing to shoot et unarmed Blacks in the streets of Soweto or Langa.

In such circumstances Mandela's reply was ready in advance : he would remain in prison. What matter the years in prison or the sordid bargain proposed by his torturers ? They were no more than jailers, but his name had already gone down to history.

He has received the highest and most solemn distinctions, and streets and squares bear his name the world over. Nelson Mandela is the holder of honorary degrees from numerous American and British universities, of the freedom of the Cities of Glasgow and of Rome, and of countless prizes and other awards. Yet he has never been honoured for what he primarily is, with every fibre of his being - a lawyer. And yet who, more than he, has ever deserved that title ?[...] "

Then Mr Favreau added :

" Your Highness,

I would like to say what an honour it is for us and with what emotion those of us who are here today, welcome you.

We know that you have travelled many thousands of kilometers to be with us, to receive this prize on behalf of your father, Nelson Mandela.

In awarding the Ludovic-Trarieux international first prize for human rights to your father, the Jury, under the aegis of the Bordeaux bar, pays hommage to one who is first and foremost the living symbol of the most odious attack ever made on the fundamental human rights.

Time, alas is insufficient to raise all the many qualities of his personality, the numerous aspects of the many battles your father has fought to defend man.

There is no one better able to accept this witness which we bear of our solidarity with barristers and advocates the world over, in their sufferance in the fight for freedom.

In accepting this Prize, Nelson Mandela has greatly honoured us, for although he has been in prison now for 23 years, He remains the freest man alive. We thank him for the honour he has bestowed upon us, by doing so.

For all that you have suffered, having been deprived of your father’s presence from an early age, for all that your mother, Winnie Mandela and your sister Zindzi, have suffered, are indeed still suffering in their shackled freedom, for all that your family have accepted to pay as a tribute to the battle of human rights, the Bordeaux bar humbly expresses, to you all, its heartfelt sympathy and warmest admiration.

But this Prize, awarded in the name of all barristers, is also presented to you by everyone of the bars in Europe and Africa, represented here with us today.

Finally, may this occasion serve as a public proof of the maintenance of the demand made by this Jury to the South African authorities, which to date has received no reply other than a contemptuous letter from the Embassy. The demand remains : " Free Mandela ! "

*Prononced on April, 27th 1985 this speech has been published in french in le Bulletin du Bâtonnier du Barreau de Bordeaux April 1985 and also in " Derrière la Cause isolée d’un homme ", Editions de la Presqu’île 1995 and in english in the " International Rewiew of Contemporary Law " Brussels 1985-1.

NOTES

SPEECH BY THE PRINCESS ZENANI MANDELA DLAMINI,

IN NAME OF HIS FATHER NELSON MANDELA,

ON OCCASION OF THE PRIZE-WINNING CEREMONY

OF THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS PRIZE

" LUDOVIC TRARIEUX "

|

|

" I am deeply conscious this afternoon that I stand here before you by default. My father upon whom you have bestowed this great honour is languishing in prison serving his second or third life sentence. My mother lives a lonely existence in primitive conditions in banishment. My sister who speaks French fluently has never been able to obtain a passport. In the c a s e of my father, his supporters have never been allowed to vote for him, but independant surveys recently have shown that 78 % of urban Blacks in South Africa regards him to be their leader. My sister and I were infants when my father went to prison and until we were sixteen years old, neither of us set eyes upon him. Even then we were only allowed to see him through a glass screen. It is only now for the last eighteen months that he has been able to hold us and we to hold him. For the past 22 years without fail my mother has travelled the long distance to Cape Town, once a month, to take advantage of the 30 visits of forty minutes each year that she is allowed. My mother who has never been convicted of any crime, lives in banishment. This is in terms of the Rule of law. |

|

The conditions of her banishment are that she may only emerge from the house during hours of daylight and remain inside over weekends and nights. Her banishment order has a number of restrictive conditions and it is only the superhuman courage of my mother and of my father that they not only survive but bear no malice to their oppressors.

The reason given for my mother’s banishmerit is that she is likely to endanger the security ot the State and the information on which, the Governement based its banishment was that, I quote, : " The informations cannot be disclosed ".

My father and my mother salute the French People for not recognizing the attempt of the South African President to seek credibility in this courntry last year, but are sad that they are persons here lured by materialism who seek to play rugby on the grounds that sport has become normal. One token Black face in a South African Rugby team does not make it integrated. At National level, racism in sport remains rife.

French investors tempted by vasts profits to be made care little about morality. Foreign investment in South Atrica merely entrenches apartheid.

The South Atrican Government has for many years waged and recently intensified, its campaign of disinformation, pretending that the situation is complex.

What is complex about a Coloured man who is killed by a White Policeman in the presence of a large number of other Policemen. The crime of the Coloured man was that he was walking in a public street with a White woman. The Policeman was fined thirty rand ?

What is complex about one traffic offender being fined two hundred rand and another being fined fifty rand for the same offence ? This is on the same day, by the same Magistrate, in the same Court. The only difference was that the former was a Black man and the latter was a White man.

What is complex about peaceful demonstrators being shot in the back ? Some as young as eleven ?

What is complex about a country where effective control still remains exclusively in White hands ?

What is complex about an economy where the haves are all White and the have-nots are all Blacks ?

My father whom yau ha-ve honoured today does not accept the honour himself, but in a representative capacity for the oppressed People of South Africa. The People of South Africa are grateful to you, frinds unknown, who care about oppression sufficiently to recognize the oppression and express by word and by action your outrage against and your abhorrence of apartheid.

My father's power has been recognized for many years by the minority Government and earlier this year they made an offer of freedom to my father.

My father gave his reply to the People.

He said that he was not a violent man.

He said that his colleagues and he had in 1952 written to Prime Minister Malan asking for a Round Table Conference to find a solution to the problems of South Africa. That was ignored.

Some years later they wrote to the Prime Minister Strydom. The same offer was made. Again it was ignored.

In the early 1960’s when Verwoerd was in power they asked for a National Convention for all the People of South Africa to decide on their future. This too was in vain .

My father told the State President P.W. Botha to show that he was different to his predecessors.

He called on Botha to renounce violence.

He called on Botha to say that he would dismantle apartheid.

He called on Botha to unban the People’s Organization, the African National Congress.

He called on Botha to free all those who have been imprisoned, banished or exiled for their opposition to apartheid.

He called on Botha to guarantee free political activity so that the People may decide who will govern them.

My father said that he cherished his own freedom dearly, but he said that he cared even more for the freedom of the People.

He said that too many had died since he went to prison. That too many had suffered for the love of freedom. He owed it to their widows, to their orphans, to their mothers , and to their fathers who had grieved and wept for them.

He said it was not only he who had suffered during these long lonely wasted years. That he was not less life-loving than the People, but he could not sell his birthright nor was he prepared to sell the birthright of the People to be free. He regarded himself to be in prison as the representative of the People and of the African National Congress which was banned.

He asked what freedom was he being offered whilst the Organisation of the People remained banned ? He asked what freedom was he being offered when he may be arrested for a "pass" offence. ? What freedom was he being offered to live his life as a family with my mother who remained in banishment in Brandfort ? What freedom was he being offered when he must ask for a permission to live in a city ? What freedom was he offered when he needed a stamp in his "pass" to seek work ? What freedom was he being offered when his very South African citizenship was stripped andth African Citizenship was stripped and he was regarded a citizen of a Homeland ?

He added that only free men could negociate. That prisoners could not enter into contracts.

My father said that he cannot and will not give any undertaking at a time when he and the People of South Africa are not free. His freedom and the Peoples freedom cannot be separated. He ended his answer by saying that he will return.

I want to say tank you to the Bordeaux Bar.

Thank you France. "

Copyright ©1999 by HRIBB. All rights reserved.

You may reproduce materials available at this site for your own personal use and

for non-commercial distribution. All copies must include the above copyright notice.

|

|

|